The Origins of Skylab

Fifty years ago, the United States launched its first space station

Exploring the intersection of spaceflight history, pop culture, and space art.

This month Creating Space commemorates fifty years since the launch of Skylab, the United States’ first space station. I look back at how the idea for Skylab began and how its early design evolved. I also share a rare model of an early orbital workshop configuration. In later posts, I plan to show how the Skylab configuration matured and share more models and period artwork. I am thrilled to let you know that Creating Space has surpassed the one-hundred subscriber milestone!

Are you new to Creating Space? It’s the NERDSletter that explores the intersection of spaceflight history, pop culture, and space art. You can find this and all other posts at creating-space.art.

The Apollo Applications Program

During the past five years, spanning 2018 through 2022, spaceflight history enthusiasts were commemorating fiftieth anniversaries of the Apollo lunar missions. Now, in 2023, we mark fifty years since the launch of the United States’ first space station, Skylab, and the three crewed missions that sent astronauts to occupy the orbiting workshop.

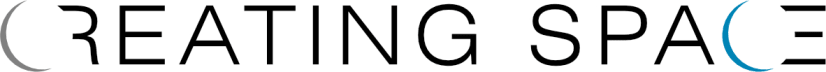

What may not be commonly known by people other than the most dedicated NASA enthusiasts is that the original plans for the Apollo program included not one, but two space stations. In addition to the well-known lunar program, NASA’s outlook for the Apollo program had a parallel thread for operations in Earth orbit. In 1960, during a NASA-industry conference, George Low presented the flow chart shown here.1

The one-man Mercury program was to be followed by the development of an advanced spacecraft capable of traveling to the Moon and beyond, as well as being used with an Earth orbiting laboratory and, ultimately, ferrying astronauts to and from a space station.

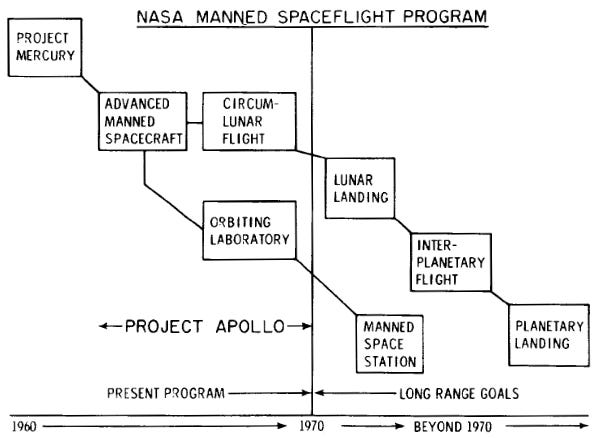

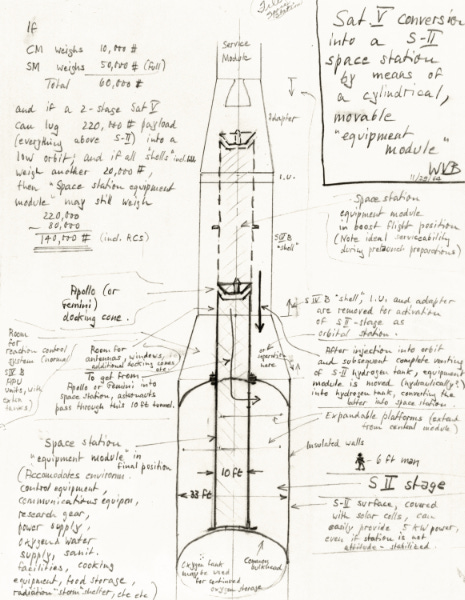

Before the Apollo Program was officially kicked off, Wernher von Braun was thinking about how to convert a rocket into a space station. The first viable plans for a working space station for the United States can trace their roots to a 1959 proposal by Wernher von Braun, who at that time was head of the Development Operations Division at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency. It was part of Project Horizon, which had as its main goal landing men on the Moon.2

When the planning for Apollo was in full swing, von Braun proposed using the ample volume provided by an empty upper stage of a Saturn V rocket. This distinctive characteristic – the use of a rocket stage as an orbiting laboratory – would ultimately be adopted for Skylab.

The Apollo lunar landings took precedence over the orbital laboratory and space station. When the final three planned lunar landing missions were canceled, NASA found themselves with surplus flight hardware. Jumping off the ideas of von Braun, NASA set out to convert a Saturn V third stage into an orbital workshop. This would be the first implementation of a variety of potential uses for Apollo hardware in what was called the Apollo Applications Program.

In 1966, during a meeting at the Marshall Space Flight Center, George Mueller, NASA Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, sketched out the final conceptual layout for Skylab.3

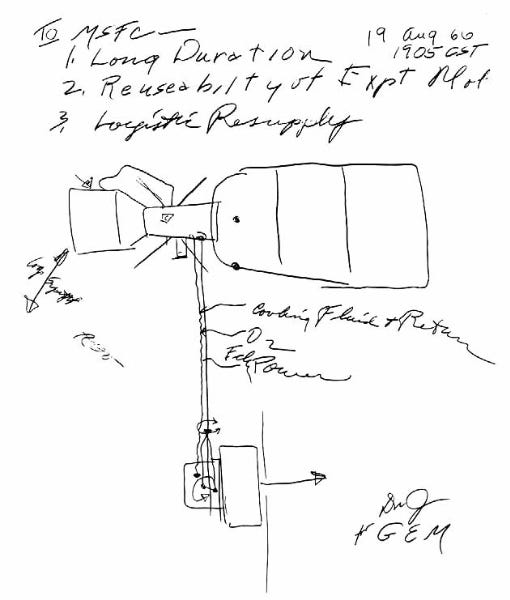

Referred to as the ‘Wet Workshop’ concept, the Saturn V third stage would initially be filled with liquid hydrogen fuel and liquid oxygen. Its engine would put the workshop into its final Earth orbit. Once there, the unused hydrogen would be vented and replaced with a breathable air mixture. Initially, the astronauts would build out the interior of the tank with equipment, but that idea was later abandoned for the simpler approach of outfitting the workshop prior to stacking on the launch vehicle on the ground. The engine would eventually be dropped from the design and the workshop would be launched without any propulsion fuel or oxygen.

An Apollo Command and Service Module would dock to an airlock at the top of the workshop (shown at left in the following diagram). Access to the docking port would be revealed by deploying the Spacecraft Lunar Module Adapter (SLA) petals. Surrounding the docking tunnel would be a so-called Spent Stage Experiment Support Module (SSESM). The interior of the workshop would consist of a ‘free volume’ surrounded by netting which the astronauts would use as hand holds to move about the workshop. Crew quarters, workstations for controlling experiments, and a galley were contained in the aft end (engine side) of the workshop.

This engineering drawing provides details about the early Skylab configuration.4

The Skylab orbital workshop configuration would evolve from there ... more on that in a future post.

Model of the Month

This model represents an early conceptual configuration for what was to become the Skylab orbital workshop. This is the only example of such a model that I have ever seen. It is quite unique among my collection of contractor models, given its material makeup and construction. As is the case with many of the models I have acquired, this configuration was unfamiliar to me and has prompted me to learn more about early space station programs.

I acquired the model from a seller who, in turn, had bought it from an antique dealer in Huntsville, Alabama. The dealer said it came from someone who had worked for Wernher von Braun in Huntsville where the basic Skylab design was first proposed.

The model’s main components appear to be made of orange-tinted clear solid acrylic. There are two separate parts held aloft by a chrome-plated rod on a wooden base. The model measures 11 1/2 inches (29 cm) long by 3 inches (7.6 cm) in diameter.

The larger of the two sections, consisting of the workshop, is identified as a ‘SATURN S-IV B STAGE’. On the side of the stage is a label saying ‘HYDROGEN TANK’.

At the aft end of the workshop section is the S-IVB propulsion engine and the oxygen tank.

At the forward end of the workshop are metal extensions labeled ‘WORKSHOP SOLAR PANELS’. The panels look as if they have been unfolded from two of the Spacecraft Lunar Module Adapter (SLA) panels.

Connected to the forward end of the workshop, above the solar panels, is a removable Apollo Command and Service module. (NOTE: The engine is a custom replacement made of solid aluminum. The original acrylic engine had broken off prior to me acquiring the model.)

Here is a nice view looking forward along the long axis of the workshop.

I’m Dave Ginsberg, the artist behind Pixel Planet Pictures and writer of Creating Space.

I am an artist and a creative engineer with a love for teaching and passions for spaceflight, astronomy, and science. My space-inspired art portfolio can be found at pixel-planet-pictures.com.

Do you know fellow Space Geeks who might enjoy Creating Space? Invite them into this space, too!

Did you miss a post? Catch up here.

If you enjoyed this article please hit the ‘Like’ button and feel free to comment.

All images and text copyright © Dave Ginsberg, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

The Apollo Spacecraft – A Chronology, Volume 1, Through November 7, 1962, NASA Historical Series, 1969

Skylab, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Skylab&oldid=1154473250 (last visited May 14, 2023).

Skylab, Our First Space Station, NASA SP-400, 1977, ch. 1, fig. 14 (https://history.nasa.gov/SP-400/ch1.htm#14)

Skylab– A Chronology by Roland W. Newkirk and Ivan D. Ertel with Courtney G. Brooks SP-4011, 1977, fig. 43 (https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4011/part1b.htm)