A LIFE Changing Experience

Eight pages of words and pictures that set my mission for life

Exploring the intersection of spaceflight history, pop culture, and space art.

Welcome back to Creating Space, and greetings to new subscribers. This month I follow up on my last post about Grumman’s first Lunar Module design, and take a look at an issue of LIFE magazine that made an impact on my choice of career. I share an alternate version of my 3D rendering of a bubble gum machine LEM. And, I have great news about an art show this month in which my work will be displayed.

Are you new to Creating Space? It’s the NERDSletter that explores the intersection of spaceflight history, pop culture, and space art. You can find this and all other posts at creating-space.art.

Model of the Month

Last month I showed you the first 1960s era spacecraft desk model that started my contractor model collection. I also promised I would share some of the items on my wish list. This is one that almost became a prized part of my collection, but is now known in my household as the one that got away. I barely missed out on buying this gem in an auction several years ago. I am hoping it, or one like it, shows up again sometime.

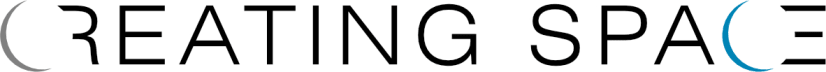

This model depicts the 1962 proposal by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation for Apollo’s Lunar Excursion Module. It stands just over six inches (155 cm) tall – substantially larger than the Lester Associates model featured in the previous post. The model was made by Grumman’s model shop for their bid proposal to NASA.1 It is rare to find models that represent such pivotal times from the space age. I don’t think you can get any closer to an authentic connection to U.S. space history in model form than this one.

LIFE in Space

The photo, above, of Grumman’s model was published in LIFE magazine in 1969 as part of their article about the development of the Apollo Lunar Module. I mentioned in my previous post being impacted by exposure to spaceflight images as a child in the 1960s. This issue of LIFE magazine made a firm impression on me. Specifically, it was the article featured on the cover as The daring contraption called LEM. I credit in large part this single magazine article and the eight pages of photographs within it for feeding my curiosity and launching me toward my eventual career in engineering. It fueled my interests in spaceflight, engineering, and art ... and quite possibly is the reason my office is filled with spacecraft contractor models.

The article included several photographs of Lunar Module concept models that showed how Grumman’s thinking had evolved over several years of development to form the final flown version. I can’t tell you how many times my nine-year-old self pored over those pages with fascination and wonder. To be honest, I still do from time to time. The article included photos of a crude wooden conceptual model with paper clip legs, a model of the white and blue “bubble” LEM (the model shown at the top of this post), a white 1965 revision with folding legs, and the angular silver and gold bug-like final version with its square hatch and a ladder for the astronauts to descend for their lunar surface activities.

I am currently enjoying Tom Kelly’s book, Moon Lander, in which he describes how each one of those design decisions was reached. It’s a fascinating account. For instance, Kelly recalls the light bulb moment when a member of the design team realized if they designed the cockpit so the pilots would fly the vehicle in a standing position then there would be no need to include seats and the large, heavy, curved glass windows could be shrunk down to relatively small flat triangles. The first design had five fixed-position landing legs, a choice which Kelly calls a “rule beater”2 since the legs would fit inside the Saturn V booster without the added weight and complexity of folding mechanisms. When the LEM grew due to requirements revisions Grumman stepped up to include larger deployable legs. Another weight conscious decision early on was to use ropes and pulleys as a means for the astronauts to transfer between the LEM and the lunar surface. When trial runs on a full-scale mock-up with real astronauts proved this method impractical, the engineers had to accept the weight penalty of adding a ladder. Happily for the engineers at Grumman, it wasn’t all weight-increasing changes, though. A change that actually resulted in a weight reduction was the elimination of the front docking hatch. Originally included for redundancy, it was deemed unnecessary. Its deletion meant not only the removal of the bulky tunnel and docking apparatus, but the structure of the entire front ‘face’ of the LEM could be made lighter since it no longer needed to absorb docking impact loads.

Getting back to the LIFE article, it also included images of rough engineering calculations with estimates of required masses for the spacecraft modules and their components. I later learned in school and on the job that early design engineering usually starts with simple sketches and basic physical estimates such as these.

The article did a great job of taking the reader from models and sketches right up to working hardware. There was a photograph of an actual LEM being assembled in a clean room at Cape Kennedy, as it was then called. Its skin and insulating Kapton film not yet applied, you could see the internal tanks and electrical equipment as clearly as any cutaway diagram could show.

The last two pages concluded the article with an illustration by Robert McCall depicting the much anticipated landing sequence of the Lunar Module. This dynamic image, with its own cutaway crew cabin, was icing on the cake for me. For as long as I can remember, I have always held parallel interests in engineering and art. Certainly, both sides of my young inquisitive brain were completely satisfied by the editors of LIFE that week.

Space Art of the Month

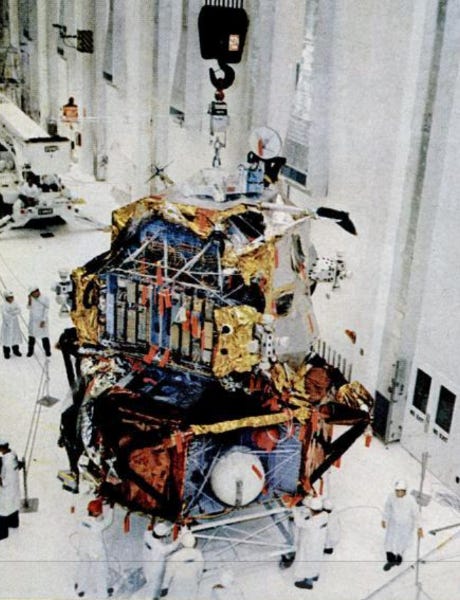

Bubble Blasted

This month’s artwork is an amusing animated extension of Bubble Blast from the previous post. After I converted the LEM into a bubble gum machine the next inspiration was to show it enjoying the simple pleasures of blowing a bubble. As has likely happened to all of us, inflation got a little out of hand and the bubble pops. Then, to add insult to injury, it lifts its leg to find a gooey gob of gum stuck to its foot. Credit goes to my brilliant wife for thinking of that gag.

Art News

Three of my works of art have been selected for display at The Art of Planetary Science (TAPS) exhibition at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory (LPL) in Tucson. As has been the case for the past decade, TAPS2023 promises to be a spectacular show featuring nearly 175 individual works from artists and creative scientists in fields including astronomy, planetary science, engineering, and space exploration. Run by graduate students, TAPS2023 is dedicated to displaying art created from and inspired by the solar system and the scientific data with which it is explored.

The Art of Planetary Science 2023: Big Worlds, Small Worlds

To be held in the Kuiper Space Science Building, located at 1629 E. University Blvd., Tucson, AZ 85721.

Opening Night: Friday (2/17) 5-9 pm

Gallery Hours: Fri (2/17) 5-9 pm, Sat (2/18) 1-5 pm, Sun (2/19) 1-5 pm

Stop by if you are in the Tucson area and check out the clear brilliant colors of my metal prints first hand. Prints will be identified for purchase at the show, and you can always find these three pieces and more of my artwork for sale in my online shop.

I’m Dave Ginsberg, the artist behind Pixel Planet Pictures and writer of Creating Space.

I am an artist and a creative engineer with a love for teaching and passions for spaceflight, astronomy, and science. My space-inspired art portfolio can be found at pixel-planet-pictures.com.

Do you know fellow Space Geeks who might enjoy Creating Space? Invite them into this space, too!

Did you miss the last post? Check it out here.

I like to learn about my readers and their interests. Feel free to leave a comment introducing yourself. Share what you like about space, space art, and a favorite item in your collection.

All images and text copyright © Dave Ginsberg, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

Moon Lander: How We Developed the Apollo Lunar Module, Thomas J. Kelly, Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001

Moon Lander, Kelly